Nicholas Plowman 包乐文

Partner 合伙人 | Legal

Hong Kong

Nicholas Plowman 包乐文

Partner 合伙人

Hong Kong

Those who do business in the PRC have long recognised the benefits of doing so through a corporate structure which enables onshore operations but offshore ownership.

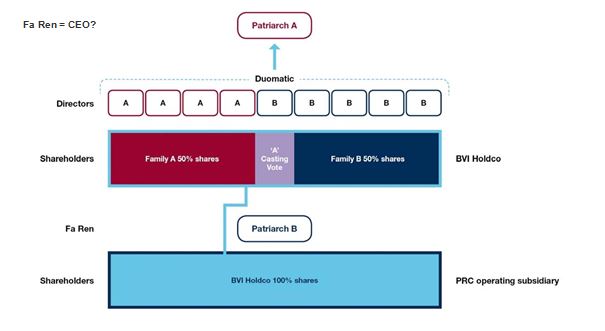

One paradigm is a structure which has a BVI Holdco holding a PRC operating subsidiary. Within this structure, the stakeholders in the PRC operations are shareholders and directors of the BVI Holdco. In many cases, they will also be parties to a shareholders' agreement governing their mutual rights and obligations.

The benefits of this structure when everyone gets on and the business is prospering, are well known. Indeed, it is for such benefits that the structure would have been set up in the first place.

What is perhaps less well-known are the benefits which the off-shore (BVI) element can offer if the participants fall out and dispute resolution becomes necessary.

When a dispute arises, the initial instinct may be to litigate in PRC. After all, that is where the real business is carried on, and usually where the stakeholders are based. However, many steps can be taken in the BVI at Holdco level to influence or dictate the outcome of the dispute in the PRC.

All these steps have one central theme: control of the Holdco - seizing control if you can, asserting control if you have it, or disrupting control if you don't. The rationale is simple and obvious: because the Holdco owns the PRC subsidiary, control of the Holdco will result in control of the PRC subsidiary.

1. Under BVI law, the instruments which confer control are:

2. Subject to specific provision to the contrary in the company's constitution and/or any shareholders' agreement, the starting position is that

3. It is possible to shift this balance of power and/or control how the powers are exercised by shareholders and/or directors, by inserting appropriate provisions in the constitution of the company and/or through shareholder agreements.

4. As between shareholders, there is another balance of power at work. This pivots on rights given by the legislation, the company's constitution and/or any shareholders' agreement to shareholders to buy each other out and/or sell each other out to a third party.

5. Control of the Holdco therefore lies firstly in careful negotiation and drafting of the company's constitution and any shareholders' agreement at the time the structure is first set up; and secondly in how one exploits the specific provisions that confer control in order to attack or defend the composition and/or decisions of the board of directors, the composition and/or decisions of the shareholders as a corporate decision-making body, and the interests of the shareholders as individual stakeholders.

6. Corporate governance measures are a favourite and familiar tactic (eg replacing directors, altering the constitution, forcing the buy-out of dissenters), and the key tools are votes, meetings and resolutions. There is a considerable body of BVI law dealing with the formal and substantive criteria for calling and conducting meetings, voting, and passing resolutions, and the consequences which flow from the failure to comply with these criteria.

7. In support of and in addition to corporate governance measures, BVI legislation and case law confer substantive causes of action and remedies, the most notable of which are

9. The structure was a BVI Holdco owning a PRC WFOE.

10. The PRC WFOE carried on business in PRC.

11. In the PRC,

12. In the BVI,

13. There had also been an agreement between Family A and Family B that Patriarch A would be the 'Fa Ren'3 of the BVI Holdco. However, 'Fa Ren' are not a feature of BVI company law.

14. Misgivings arose as to how the business was being operated in PRC. There were suspicions that WFOE money was being diverted to the pockets of Family B. However, as Patriarch B was the Fa Ren of the WFOE, it was thought that direct action in PRC would encounter difficulties, unless steps were first taken at the BVI level.

15. The aim was to take control of the BVI Holdco at board level because this would give control of the business decisions of the BVI Holdco.

16. Since the BVI Holdco was the sole owner of the WFOE, control of the BVI Holdco was control of the sole owner of the WFOE and therefore control of the WFOE.

17. Patriarch A called a meeting of shareholders of the BVI Holdco to change the constitution of the Holdco and to change the voting requirements at board level, the effect of which would be to give Family A control of the Holdco at board level.

18. In calling that meeting of shareholders, Patriarch A did so in his capacity as director of the Holdco, not in his capacity as shareholder of the Holdco. Under BVI law, directors can call shareholder meetings whenever necessary or desirable, but shareholders can only ask the directors to call shareholder meetings in certain circumstances.

19. Notices of the meeting were sent out to all shareholders, but no one from Family B attended the meeting. At the meeting, Family A passed resolutions to change the company's constitution and the voting requirements at board level, and thereby obtained board control.

20. Family B subsequently challenged the validity of these changes, claiming that they had not received notice of the meeting. Patriarch A claimed that he had sent the notices by courier, but Family B claimed that there were no notices in the packages they received.

21. Since the documentary evidence was inconclusive, the BVI Court had to decide who was telling the truth, and it decided that no notices had been sent or received. Therefore, the meeting was invalid and the purported changes were null and void.

22. In the sequence of events recounted above, the control that was targeted was control of the board of directors of the Holdco, and this was sought to be achieved by deploying votes at shareholder level.

23. Because Patriarch A had the casting vote, he and Family A were guaranteed to succeed in implementing the changes they desired, provided the meeting that had been called was a valid meeting. However, the process by which Patriarch A caused notices of the meeting to be prepared and served was insufficiently rigorous to withstand challenge, with the result that, "for want of a nail, the Kingdom was lost."4

24. The need for rigour in the fight for control is not confined to administrative tasks, nor are administrative tasks typically the area where victory or defeat is to be found. The need for rigour extends to ensuring that all specified formalities, time-lines and wordings are interpreted correctly and applied properly, and in the majority of cases, this is the real battleground, as the next 6 paragraphs illustrate.

25. What had not been considered by Family A was the possibility that control might already have resided in Patriarch A alone, by virtue of the previous agreement that he was the 'Fa Ren' of the BVI Holdco.

26. Since 'Fa Ren' are a feature of PRC law but not BVI law, it was not immediately obvious that a PRC agreement for Patriarch A to be the Fa Ren of the BVI Holdco would have any effect of recognition in BVI.

27. However, BVI legal principles potentially offered a route to the same outcome. Under BVI law, corporate decisions which can and should be made by formal shareholder or board resolutions can also be made by the shareholders or directors agreeing informally and unanimously. This is known as the Duomatic Principle.

28. At the same time, a common provision in the constitution of BVI companies is that the board of directors may appoint officers of the company, such as a CEO, to whom is delegated such powers of the board as the board chooses. There was such a provision in the constitution of this BVI Holdco.

29. The individuals who had agreed that Patriarch A should be the Fa Ren of the BVI Holdco also happened to be all the directors of the BVI Holdco.

30. On these facts therefore, a reasonably good argument could be made that there had been an informal and unanimous (Duomatic) board decision to appoint Patriarch A as the CEO of the BVI Holdco, delegating to him powers which were equivalent to the usual powers of a PRC Fa Ren.

31. The strategies described above would be of little or no practical value without a legal system and judiciary of commensurate quality.

32. The BVI was originally a British Colony and is now a British Overseas Territory. Its legal system is derived from and based on the English legal system, and its laws are therefore a mixture of legislation and case law.

33. BVI legislation is a combination of a) locally passed statutes (a significant proportion of which replicate or adapt English statutes); and b) English statutes made directly applicable to the BVI by Orders in Council of the English Parliament.

34. As for case law, it is expressly enacted by the Common Law (Declaration of Application) Act (Cap 13) that English common law applies in the BVI. There is also a healthy and increasingly growing body of BVI case law built upon English common law.

35. The BVI judicial system is modelled on the English system. Generally, matters relating to international business companies and intellectual property fall within the jurisdiction of the BVI Commercial Court, which is a specialist division of the BVI High Court of Justice. The Commercial Court is presided over by the Honourable Justice Bannister QC, who was recruited to the position from London, where he had practised for many years as Queen’s Counsel specialising in company, chancery and commercial law.

36. The BVI Commercial Court frequently hears and adjudicates on complex, high-value international disputes involving BVI companies, in which the parties are typically represented by international law firms based in the BVI (whose practitioners are usually qualified and trained in England) and by eminent Queen's Counsel from London. Overall, the BVI Commercial Court offers a forum whose procedures, hearing environment and judgments are very similar to those of the High Court of Justice in London, and it is highly regarded locally and internationally by parties and practitioners who have appeared before it. Appeals from decisions of the BVI Commercial Court lie to the Eastern Caribbean Court of Appeal, and from there to the Privy Council in London.

[1] in order to preserve confidentiality and keep the example short, certain aspects have been modified or omitted.

[2] the difference can be significant if the parties have agreed that certain decisions can only be made with a 75% majority and not a 50+% majority.

[3] A 'Fa Ding Dai Biao Ren' (Fa Ren, or Legal Representative) is the individual authorised and recognised under PRC law as having executive power and autonomy to manage and conduct the business and affairs of a PRC company.

[4] an old proverb said by many to refer to the loss of the realm upon the death of King Richard III of England at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. In full, the proverb is as follows:

"For want of a nail the shoe was lost. For want of a shoe the horse was lost. For want of a horse the rider was lost.For want of a rider the message was lost. For want of a message the battle was lost. For want of a battle the kingdom was lost. And all for the want of a horseshoe nail."

Ogier is a professional services firm with the knowledge and expertise to handle the most demanding and complex transactions and provide expert, efficient and cost-effective services to all our clients. We regularly win awards for the quality of our client service, our work and our people.

This client briefing has been prepared for clients and professional associates of Ogier. The information and expressions of opinion which it contains are not intended to be a comprehensive study or to provide legal advice and should not be treated as a substitute for specific advice concerning individual situations.

Regulatory information can be found under Legal Notice

Sign up to receive updates and newsletters from us.

Sign up